Coulter Department News

Coulter Department News

Commercialization program in Coulter BME announces project teams who will receive support to get their research to market.

Courses in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering are being reformatted to incorporate AI and machine learning so students are prepared for a data-driven biotech sector.

Influenced by her mother's journey in engineering, Sriya Surapaneni hopes to inspire other young women in the field.

Coulter BME Professor Earns Tenure, Eyes Future of Innovation in Health and Medicine

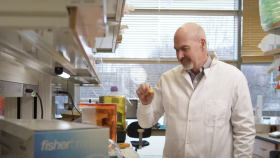

The grant will fund the development of cutting-edge technology that could detect colorectal cancer through a simple breath test

The surgical support device landed Coulter BME its 4th consecutive win for the College of Engineering competition.

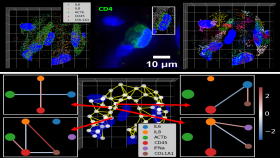

New research from Georgia Tech helps doctors predict how therapies will interact with a child's immune system, potentially improving outcomes and reducing risks.

Georgia Tech researchers reveal the dynamic role of inhibitory neurons in spatial memory and learning

The department remains a top-ranked biomedical engineering program for graduate education in the nation.

Neuroscientist and former BME grad student Nuri Jeong is helping to reshape lives and careers

Georgia Tech authors reflect a rapidly evolving field in new edition highlighting real-world applications

Hands-on approach to teaching microfluidics is inspiring future innovators

In this edition of Ferst Exchange, Coulter BME's Aniruddh Sarkar explains the science.

Georgia Tech researchers uncover the role of lateral inhibition in enhancing contrast and filtering distractions, with implications for neuroscience and AI.

Graduate BME students are tackling heart disease and training to become leaders and innovators in cardiovascular research

BME undergrad is first student from Coulter department and one of three from Georgia Tech to earn aerospace honor

Coulter BME researchers develop 3D-printed, bioresorbable heart valve, potentially eliminating the need for repeated surgeries.

The 2007 BME alum will lead efforts to bring medical technologies to market.

BME graduate leveraging Coulter experience to bridge continents and inspire students

Seven other Faculty Members from Coulter Department Named to Fall 2024 Honor Roll

Researcher Michaël Girard delivers eye-popping presentation at BME Seminar Series

Anant Madabhushi part of Emory team awarded up to $17.6 million to innovate surgery, improve outcomes

BME researchers combine precision and simplicity in transforming diagnostic tools.

Researchers demonstrate stem cell treatment without chemotherapy and painful bone marrow procedure

BME researchers explore the critical role of mechanical force in rare genetic disorder

Researchers develop spatial transcriptomics toolkit that provides new insights into the molecular processes of life

Air Detectives take top prize to give department three straight victories in Expo competition

Coulter BME community gathers at the Fabulous Fox to celebrate anniversary of unique public-private partnership

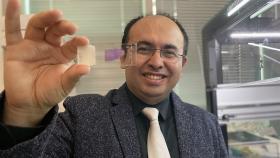

Coskun pioneering new research area and building a company around iseqPLA technology

BME undergraduate student and competitive skater Sierra Venetta has found success on and off the ice