Mice have a bad and undeserved reputation as an animal that can’t see very well, a characterization upheld most notably (and somewhat tragically) by the song Three Blind Mice. And also by the fact that mice really can’t see very well (they resolve less detail in a visual scene than humans).

But, they see well enough to quickly detect visual stimuli throughout their visual fields. Bilal Haider says this makes mice an excellent model system, “for studying how neural circuits mediate rapid visual behaviors – mice are a very good model for studying what can happen in humans making fast decisions about visual information.”

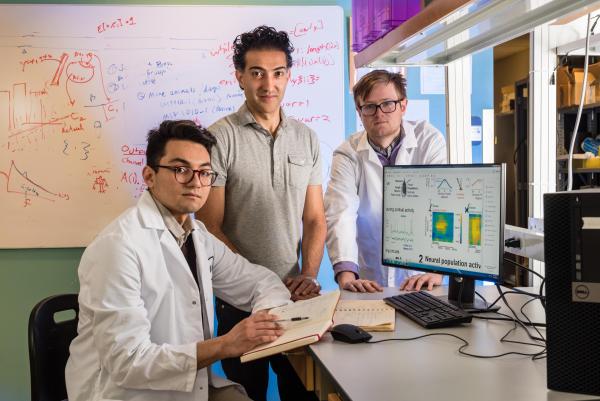

Haider, assistant professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University, and his colleagues prove the value of mice while demonstrating how the brain visually detects and perceives visual stimuli in their latest research, entitled “Cortical State Fluctuations across Layers of V1 during Visual Spatial Perception,” published recently in the journal Cell Reports.

“This paper shows that mice can detect a small, faint object appearing very briefly and unpredictably in the visual field, and they can respond to this stimuli in less than half a second, and make a precise motor response,” explains Haider, corresponding author of the paper, whose co-researchers on the project were lead authors Anderson Speed and co-author Joseph Del Rosario, grad students in his lab, and Christopher P. Burgess, a researcher at Google DeepMind in the UK.

“Actually, mice have a very fast visual system to produce actions, not that much slower than ours,” Haider adds.

In the paper, the authors explain that behavioral factors like sleep, wakefulness, and movement have strong effects on the state of cortical activity. And while Haider and others have previous established that cortical states have profound effects on sensory responses, there remain unresolved questions about cortical states and their effects on the speed and accuracy of sensory perception.

So, to address the questions they trained mice to detect visual stimuli appearing in discrete portions of the visual field. And they simultaneously measured local field potentials (an electrophysiological signal generated by the electric current flowing from large populations of neurons) and excitatory and inhibitory neuron populations across layers of the primary visual cortex that receives visual information.

Through their experiments, Haider’s team showed that changes in cortical activity states exert strong, widespread effects in a mouse’s primary visual cortex, and can play a prominent role for visual spatial behavior. Haider’s team could use this neural activity to “mind read” and accurately predict perceptual outcomes.

Basically, the team figured out, Haider says, “that the properties of the visual system in mice, especially the way they use vision for behavior, and the neural activity that we see in their visual system, is remarkably similar to what’s seen in primates and humans. This will allow us to use the mouse as a platform for studying neural circuits underlying visual dysfunctions in models of neurological diseases.”

Media Contact

Jerry Grillo

Communications Officer II

Parker H. Petit Institute for

Bioengineering and Bioscience

Latest BME News

Jo honored for his impact on science and mentorship

The department rises to the top in biomedical engineering programs for undergraduate education.

Commercialization program in Coulter BME announces project teams who will receive support to get their research to market.

Courses in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering are being reformatted to incorporate AI and machine learning so students are prepared for a data-driven biotech sector.

Influenced by her mother's journey in engineering, Sriya Surapaneni hopes to inspire other young women in the field.

Coulter BME Professor Earns Tenure, Eyes Future of Innovation in Health and Medicine

The grant will fund the development of cutting-edge technology that could detect colorectal cancer through a simple breath test

The surgical support device landed Coulter BME its 4th consecutive win for the College of Engineering competition.