A group of Georgia Tech researchers has discovered a new type of molecular interaction that could have important implications in preventing the spread of tumors and cancerous cells.

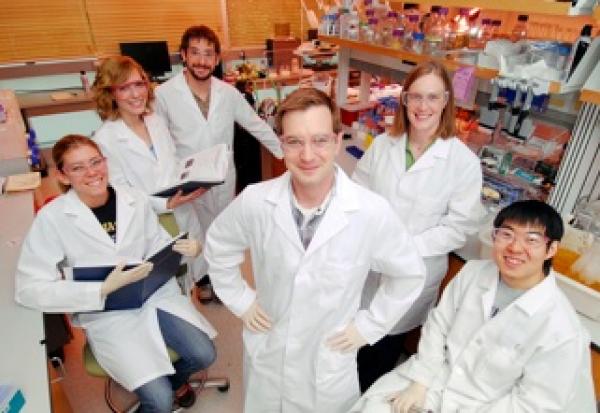

Working within Georgia Tech’s Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, the researchers found a unique trimolecular relationship between Thy-1, a lipid tether protein; α5β1, a transmembrane receptor; and Syn-4, another protein.

“When Thy-1 bonds with α5β1, they form what’s known as a slip bond, which is easily broken apart when force is applied. The same thing happens between Thy-1 and Syn-4,” said Dr. Thomas Barker, one of the lead authors. “But what we observed is that when all three molecules come together, they form what we call a catch bond. Instead of breaking apart when force is applied, a catch bond becomes stronger, almost like a finger trap.”

The findings from Barker, Vincent Fiore, Lining Ju, Yunfeng Chen, and Dr. Cheng Zhu appear in the journal Nature Communications.

The research that led to the findings began as a weekend project sparked by one graduate student’s curiosity — a chance observation that turned into a full-scale research project.

“One of my classmates and I set off to try to understand how integrin receptors bind Thy-1 on a cell’s surface,” said Fiore, student researcher in Barker’s lab. “What we observed was this new receptor of Thy-1, and a new type of interaction neither of us had seen before.”

The group’s findings have implications for stopping the spread of cancerous tumors and healing persistent wounds, Barker said. Thy-1is a so-called “recruitment protein.” From its position on the outside of a cell, Thy-1 can “capture” other proteins that are flowing through the bloodstream. When a doctor removes a tumor, for example, the tumor itself is gone, but cancerous cells may still be present in the bloodstream. These findings demonstrate the potential to disrupt the interaction between an endothelial protein and the circulating tumor cell receptor that causes tumor metastasis.

“These findings could have implications for physicians treating unhealing wounds,” Barker said. “This understanding could be used to engineer stem cells to actively home to the unhealing region by injecting stem cells into the blood stream.”

To read the full findings in Nature Communications, click here.

Written by Chris Calleri

Media Contact

Chris Calleri

Communications Manager

Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering

Georgia Institute of Technology & Emory School of Medicine

313 Ferst Drive, Suite 2120

Atlanta, GA 30332-0535

Phone: 404.385.2416

Keywords

Latest BME News

Jo honored for his impact on science and mentorship

The department rises to the top in biomedical engineering programs for undergraduate education.

Commercialization program in Coulter BME announces project teams who will receive support to get their research to market.

Courses in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering are being reformatted to incorporate AI and machine learning so students are prepared for a data-driven biotech sector.

Influenced by her mother's journey in engineering, Sriya Surapaneni hopes to inspire other young women in the field.

Coulter BME Professor Earns Tenure, Eyes Future of Innovation in Health and Medicine

The grant will fund the development of cutting-edge technology that could detect colorectal cancer through a simple breath test

The surgical support device landed Coulter BME its 4th consecutive win for the College of Engineering competition.